In their respective eras, Pele and Lionel Messi took the field while wearing the crown as the greatest soccer player of all-time. Among the many feats these two global icons have in common is that neither of them could score a goal in Cleveland.

57 years before Messi came to Huntington Bank Field for a Major League Soccer match against the Columbus Crew on April 19, 2025, Pele and his famed Brazilian club, Santos, played on the same patch of land in an exhibition match against the North American Soccer League’s Cleveland Stokers on July 10, 1968.

In both cases, there was money to be made and a sport to grow. But unlike Saturday’s orderly event, the 1968 game at Cleveland Municipal Stadium featured an on-field riot in the closing moments. A disallowed goal in the 89th minute that would have tied the game for Santos sent the visitors over the edge. They physically took out their frustrations on the game officials and the fans in the stands as the remaining clock bled out, sealing Cleveland’s shocking 2-1 victory.

“Boy oh boy, they were upset,” says Roy Turner, the Stokers’ left halfback, now 82, from his home in Wichita, Kansas. “It totally shocked me and it totally shocked a lot of people.”

*****

The Cleveland Stokers formed in 1967 in the United Soccer Association, which aimed to capitalize on stateside soccer interest generated by the 1966 World Cup. To form a league—with a patriotic USA abbreviation!—on such short notice, the circuit imported foreign teams wholesale for a brief summer season. Cleveland welcomed English club Stoke City, thus the Stokers name.

In 1968, the USA merged with the National Professional Soccer League to form the North American Soccer League, which would eventually usher in a brief but highly memorable era in America’s soccer growth. With the formation of the NASL, teams were on their own to sign players for the 1968 campaign. Cleveland capitalized by bringing in a few notable international players, such as defender Ruben Navarro from Argentine club Independiente, and striker Enrique Mateos, who played eight seasons with Real Madrid. Even though Cleveland was no longer affiliated with Stoke City, the Stokers name remained.

The club got off to a good start and by midsummer they were in second place in the NASL’s Lakes Division, with a record of eight wins, four losses, and seven draws.

“We had a tremendous group of players from all walks of life,” says Turner, who grew up in Liverpool, England. “We had two great international players in Mateos and Navarro. We all got along quite well.”

The Stokers attracted a little over 4,000 fans per game. Despite that number’s modesty, it was in the top half of the league as professional soccer tried to get off the ground again in America. Regardless of context, a typical Stokers crowd easily got lost in Municipal Stadium’s mammoth structure, with a capacity of 80,000 and the front row of the lower-level midfield seats being situated roughly 40 yards from the touchline.

“It was very difficult to get any atmosphere going in that stadium, although the people tried their best,” Turner says. “It was a huge stadium and there would be three or four thousand people there.”

With Santos touring the United States in the summer of 1968, the Stokers turned to the oldest trick in the book for growing an American soccer audience—selling tickets to see the most famous player in the world.

*****

Compared to the months-long build-up to Messi’s Cleveland appearance, Pele’s pending arrival was given a mere two weeks of lead time. The Plain Dealer’s sports page on June 26, 1968, decreed via headline: “World’s Greatest Soccer Player Pele to Play Here.” The match was scheduled for 8:00 p.m. on July 10.

Led by Pele, Santos was the two-time defending world club champion. Pele had also led Brazil to victories in the 1958 and 1962 World Cups.

In the event such on-field accomplishments meant little to the general public, the Cleveland media breathlessly reported that Pele was the world’s highest paid athlete with an annual salary of $400,000 and an additional $400,000 per year in endorsement income, all tax-free in Brazil because he was officially declared by the government to be a national treasure. His combined haul was the equivalent of $7.3 million in 2025 dollars, and it dwarfed all other athletes of his era. The Plain Dealer noted that American sports heroes such as Jack Nicklaus ($200,000), Oscar Robertson ($115,000) and Willie Mays ($100,000) earned substantially less than Pele.

Plain Dealer reporter Bill Nichols sold the money angle, writing on July 4, 1968, “You’ll see firsthand what a millionaire soccer player does for his pay. How can an individual get that kind of money just for playing soccer? Well, to begin with, soccer in Brazil is not just a game, it’s a national disease.”

[The Alzheimer’s of athletics! The Crohn’s of competition! The syphilis of sport!]

Also on July 4, PD columnist James E. Doyle presented various questions in the form of poems, then answered them. There was one about Pele, attributed to Woodland Hill Billy:

My old man, slightly off his rocker

About the ancient game of soccer,

Says Top Kick Pele ought to fill

The Stadium. You think he will?

Doyle responded, “Well, there’s no doubt the famed Brazilian Santo star, who has a Santa clause in his contract, will draw a record Cleveland soccer crowd next Wednesday night. Ten thousand, perhaps?”

That’s another modest number, but it was a different time. Pele and Santos pulled 43,002 fans to Yankee Stadium for a game against Italian champions Napoli, but most games on the American tour were attracting 15-20 thousand onlookers. Those were gangbusters numbers for soccer in America at that time.

Although Pele’s presence offered a lucrative opportunity and required a large cash outlay to book the match, the Stokers opted to keep the ticket prices the same as for any regular season game. Tickets were $5 for upper boxes, $4 for upper reserved, $3 for the entire lower deck, and $1 for bleacher seats. (That sounds exceptionally cheap, but those prices ranged from $9 to $46 in 2025 dollars, which actually is exceptionally cheap compared to seeing Messi play anywhere in America. Tickets for the Cleveland game were triple digits.)

Stokers General Manager Marsh Samuel told the Plain Dealer, “We are aware that other cities have scaled their prices between $4 and $10 to see Santos and Pele, and they are getting a good response. However, our owners, Howard Metzenbaum and Ted Bonda, are more interested in making new fans for soccer than they are in the single large gate.”

Just as Messi’s appearance was intended to introduce Clevelanders to Columbus Crew soccer, the concept of using a global superstar as a gateway for supporting the local team is not a new one. On July 7, Mrs. John L. Lyons (her actual name was apparently unimportant in 1968) of Rocky River wrote a letter to the editor encouraging soccer fans to use the Santos-Stokers match to grow the game.

She wrote to the Plain Dealer: “Since it so very important to the success of soccer here that we have a large attendance on July 10 when Pele ‘The King of Soccer’ plays, may I please make a simple suggestion? If every REAL soccer fan would definitely take one EXTRA guest to the game, it would work like the ‘Domino Theory’ and soon build up till we had a good morale builder for the Stokers.”

While the Stokers and their fans seemed to be taking a more altruistic approach to the match, it was Santos who appeared to be going for the cash grab. They were exploiting the American tour for every last penny of appearance fees and gate percentages they could get their hands on. Being forced to physically endure ten games in the span of just 23 days, one could only hope the Santos players were sharing in the profits.

The itinerary was so brutal and illogical it would get any travel agent fired. Here was Santos’ schedule in the week leading up to the Cleveland game:

Thursday, July 4: Santos 4, Kansas City Spurs 1 (Kansas City, MO. Att: 19,126)

Saturday, July 6: Santos 4, Necaxa 3 (Los Angeles, CA. Att: 12,418)

Monday: July 8: Santos 7, Boston Beacons 1 (Boston, MA. Att: 18,431)

Wednesday, July 10: Santos at Cleveland Stokers

Despite the wear and tear of the relentless schedule and zigzagging cross-continental travel, Santos came to Cleveland with a record of 7-0-0 on their North American tour. More of the same was expected that Wednesday night.

*****

The morning of the game, Nicholls wrote in the Plain Dealer that Santos “is here to show the homefolks just what worldwide soccer is all about. And there is no better teacher than Pele.”

Pele said that St. Louis and Kansas City were the two best NASL teams Santos had faced so far, and he was happy with how the tour was going.

“American people are understanding the game of soccer very well and seem to like it,” he told the Plain Dealer. “In one or two years it should be a very big success here.”

As for Cleveland, Pele was cool with it.

“This is my first time in Cleveland,” he said, “but I want to come back as a tourist.”

That was before the melee to come.

*****

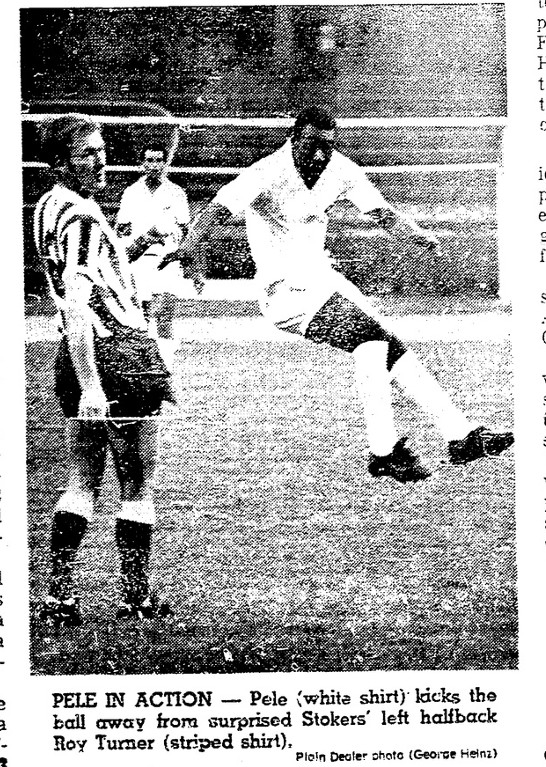

Turner was tasked with marking Pele in the match, and in a joint team photo before the game, he clearly started shadowing his mark early. Pele is in the center with the soccer ball at his feet. To our right, Pele has his left arm around Turner, who was glued to his hip before the match even started.

It was a daunting assignment for Turner, even with Navarro assisting in the defending. He relied on the experience and advice of Navarro to settle his nerves about marking the world’s greatest player.

“I knew it would take some effort to try to stop him because he is the best, so there was a lot of nervousness going in,” Turner says. “I had people around me who calmed me down and were very comforting. There’s nothing different I did, other than giving more respect to any player than I ever had. I was pretty successful, although I did see a lot of the back of his shirt.”

In front of a local record soccer crowd of 16,205, Cleveland took a 1-0 lead in the 27th minute on a penalty kick goal by Mateos, who drilled his shot into the upper right corner. The Stokers carried that lead into the interval, but Santos equalized early in the second half when Toninho chested down a pass from Pele and angled a shot into the net from nine yards out in the 51st minute.

The game turned in the 72nd minute when Santos was awarded a penalty kick and a chance to take the lead. Toninho stepped to the spot against Stokers goalkeeper Paul Shardlow. A Stoke City holdover, Shardlow returned to Cleveland to get regular game action, having made just four appearances in two years with the parent club. Already performing heroically, Shardlow made the save of the game, stoning Toninho with a diving catch on the penalty attempt.

“It didn’t take me long to realize what a hell of a talent he was in goal,” Turner says of Shardlow. “I think on that particular night, Paul was a great goalkeeper anyway, but everything clicked. He was absolutely brilliant, and you have to be in order to beat Santos.”

The Stokers would get the winning goal in the 83rd minute when forward Dietrich Albrecht of Germany beat Santos goalkeeper Laercio to a loose ball and rifled it into the empty net. The stage was then set for the explosive ending.

*****

With 1:12 to play, Toninho appeared to tie the game when he took a pass from Pele, turned, and scored from five yards out. Then the linesman raised his flag, the referee waved off the goal, and all hell broke loose.

The Santos players immediately swarmed referee Henry Landauer and then went after linesman Jack Connor, shoving both. Connor also received a swift kick from an angry Santos player. With the officials under literal assault as the Santos players chased them off the field to the rolled-up tarpaulin beside the stadium’s third base dugout, the fans tried to save Landauer and Connor, which prompted the Santos players to go after the fans. They scooped up dirt near the baseball dugout and hurled it at the spectators, with one player climbing over the railing and throwing punches into the crowd before being pulled back over by a teammate. Even Pele himself was reported to have angrily spit at fans during the fracas. Thankfully, the fans did not escalate the situation further by pouring onto the field.

News-Herald reporter Dave White wrote, “Police, who were not the most efficient group of cavaliers on this night, finally made the scene and cooled some of the heated Brazilians.”

East Liverpool (OH) Review sports editor Turk Pierce opined, “In any other country, in a league match, such a situation would have provoked a full-scale riot, but at Cleveland, there was merely booing.”

As the clock does not stop in soccer, time expired during the melee. While the officials belatedly received a police escort off the field, the Stokers had shockingly defeated the best club team in the world by a 2-1 score.

“It was like we’d just won the Super Bowl,” Turner says. “It was such an incredible feeling to beat them. Obviously, their reaction to the defeat is something I’ve thought about. What did this mean to them? Did they get a bonus for winning or something? What’s going on here? They were mad. That made the victory mean even more. It’s not like they put a team out there for a stroll in the park. They obviously wanted to win as they were one of the best teams in the world. It was a reaction that you would never expect in an exhibition game. Maybe a World Cup final, but not an exhibition game in Cleveland.”

Pele spoke out against the officiating after the game.

“The referee was wrong on the call and did a very poor job all night,” he said, adding that the referee had also officiated their match in Los Angeles. “He was very unfair toward us both times.”

With all the rancor and commotion at the end of the game following Cleveland’s startling victory, Turner never got to have the postgame interaction he had hoped for.

“I remember trying to get next to Pele and maybe even trying to get his jersey,” he says, “but I don’t think there was much sentiment to give away his jersey because he was so angry about everything else. We kind of spoiled saying goodbye and thanking him. For him, it was a disappointing evening because, while everybody loved Cleveland, they wanted to see Pele score. That’s what they came for, and it didn’t happen.

“I can take a little credit for that.”

*****

Epilogues

Here are some things that happened after Cleveland’s upset victory and the craziness that ensued on the field.

* The Plain Dealer published the following editorial on July 12, 1968:

* That same day, Dan Coughlin wrote a story that Detroit Cougars head coach Len Julians reviewed video from Lakewood’s cable TV service, which recorded Stokers games then aired them days later. He was in town reviewing video of Detroit’s recent 2-1 loss to Cleveland, but also looked at Toninho’s disallowed equalizer from the 89th minute.

“It was a good goal,” Julians told Coughlin. “The player with the ball was clearly onside.”

That’s because Toninho received Pele’s pass with his back to the goal, then spun around Navarro before firing a low shot past Shardlow’s left leg and into the net. The key, however, is that Toninho was not the player who was offside. According to Coughlin, two players on the left wing were possibly in an offside position, but the camera zoomed in just before Pele played the pass, so one could not definitively declare whether the call was right or wrong based on the available footage. (This was before the passive offside rule, so if anyone was offside on the wing, even far away from the play, the flag still should have been raised and the goal negated.)

* A week after their Cleveland tantrum, Santos did the same thing in Bogota during an exhibition match against a team of Colombian all-stars. The Colombians scored a goal that the Santos players felt was offside, so they assaulted the referee. The police in Colombia took the matter more seriously than the police in Cleveland, and they put the entire Santos team, including Pele, in jail for three hours. To secure their release, the Santos players had to write a letter of apology to the referee and the Colombian people.

When I tell Turner this story, he howls with laughter.

“Good God!” he exclaims. “I never knew that! So it wasn’t just us! I think they took the game rather seriously. Unbelievable. Oh my God. That’s incredible. They’re the best players in the world and they’re there because they won games and they don’t like to get beat.”

* Cleveland did not see a significant bump in attendance after Pele’s visit, but the Stokers would finish first in the Lakes Division with a final record of 14 wins, 7 losses, and 11 draws. They faced the top-seeded Atlanta Chiefs in the conference final and were moments away from advancing to the championship round. However, they surrendered a goal in the final seconds of extra time, then allowed another in the sudden death overtime session that followed extra time in lieu of penalty kicks. A real heartbreaker, in accordance with Cleveland sports custom.

* The Stokers’ owners, Bonda and Metzenbaum, decided to sit out the 1969 season over frustration with the league’s small-budget mindset. Despite all they achieved in 1968, the Stokers never took the field again.

“You could see the fans getting more and more into the games as the season went along because we were pretty successful,” Turner says. “I enjoyed it and it was a shame we didn’t come back to grow from where we grew in that first (NASL) season.”

* Barely three months after playing the game of his life against Santos, goalkeeper Paul Shardlow died of a heart attack on the training ground with Stoke City on October 14, 1968. He was only 25 years old.

* Lionel Messi attracted a crowd of 60,614 for his appearance in Cleveland. The Columbus Crew, who hosted the match in the larger Browns stadium to accommodate the demand, have a season ticket waitlist and routinely sell out Lower.com Field, their state-of-the-art 20,371-seat soccer stadium in downtown Columbus. It may have taken more than the “one or two years” that Pele estimated upon his arrival in Cleveland, but professional soccer in America has come a long way in 57 years.

* As for Roy Turner, he would become an NASL mainstay with the Dallas Tornado and even make two appearances with the U.S. Men’s National Team. Following his playing days, he had a successful coaching career with the Wichita Wings of the Major Indoor Soccer League.

But for one night early in his career, he went up against Pele, the greatest player in the world, and his Cleveland Stokers staged such an unfathomable upset over Brazilian powerhouse Santos that it made news across the pond in Turner’s hometown of Liverpool.

“It was the highlight of my career playing against such talent and such a gentleman,” Turner says. “I wouldn’t say it was the game of my life, but it was the most memorable game I ever played in.”

It was a riot.

Steve Sirk is a Cleveland-based author who has written four books about the Columbus Crew and is currently working on a book about the Cleveland Force of the Major Indoor Soccer League. He can be reached at sirk65@yahoo.com or via Twitter or Bluesky @stevesirk